Weimar Germany, the Russian Civil War, and the Purishkevich-Ludendorff Connection

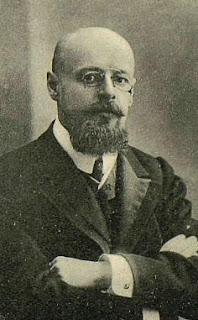

Erich Ludendorff

After the Russian Civil War had broken out, a

pro-German wing of the Russian White movement appeared in contrast to the pro-Entente

sentiment of the mainstream Russian Whites. It must have been difficult for these Russian nationalists

to forgive General Ludendorff and the Germans for aiding the Bolshevik

Revolution and overseeing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Yet, in their eyes, compared to the

Entente Powers, with their pro-Bolshevik banks and criminal negligence of their

Russian ally’s logistical needs, Ludendorff and the Germans had only been doing

their jobs.

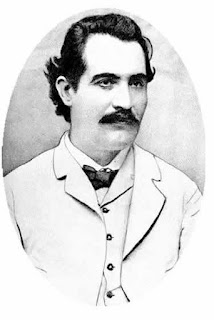

From

1918 until 1923, this pro-German wing of the Whites, initially formed by

Vladimir M. Purishkevich upon his release from prison in 1918, would heavily

influence the direction of the nationalist right in Weimar era Germany. The extent of this influence includes,

but is not limited to, the fledgling NSDAP in the years before the Beer Hall

Putsch of 1923. It also includes

the 1918 translation of The Protocols of

the Elders of Zion into German, as well as helping Ludendorff engineer the

Kapp Putsch of 1920 – the same year Purishkevich died.

In

The Russian Roots of Nazism: White

Émigrés and the Making of National Socialism 1917-1945, Michael Kellogg

covers this subject in a more scholarly way than the book’s sensationalistic

title suggests. For anyone

interested in any of the events or personalities covered in this book, it is a

highly recommended classic. The

book’s scholarly tone is always cold, but never boring.

While

Hitler himself insists in his autobiography that he became an anti-Semite in

Vienna before World War I, Kellogg formidably argues that Hitler only gained

his courage of conviction after reading The

Protocols and meeting a mysterious clique of White Russians and their

Baltic German allies. The book

also produces some surprising quotes by Alfred Rosenberg and even Hitler himself

in praise of the Russian nation, if certainly not the contemporary Bolshevik

government. However, other than describing

the Russian connections of Hitler’s mentor and favorite of the National

Socialists killed in the Beer Hall Putsch (Max von Scheubner-Richter), the book

leaves the reader somewhat in the dark as to why Hitler’s attitude toward the

Russians changed after 1923.

Many

of the figures described in this book demand their own biographies, but Kellogg

is wise not to turn the book into one.

Without a biographical focal point, the book coldly allows the

distressed age to become the main character. The Russian Roots of

Nazism even provides illuminating information on subjects that one would

not expect from the book, such as the now-little-known views of Schopenhauer

and Dostoevsky on the Jewish question.

Despite such wide range, the book never strays far from focus.

Comments

Post a Comment